A Brief Biography

In the somber halls of academe, an individual appears who is a philosopher in the original sense of the word -- a bright lover of wisdom, a herald of higher human possibilities.

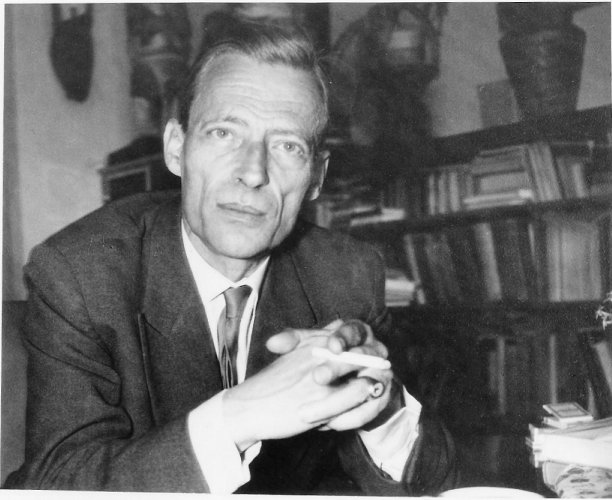

The Swiss philosopher and poet Jean Gebser belonged to that rare Socratic breed. He was a man of extraordinary vision who did not allow himself to be seduced by his learning, but intrepidly pushed beyond the boundaries of accepted truth. He likened modern philosophy to the "picking apart of a rose." His foundational work on the evolution of human consciousness and culture is among this century's finest contributions to our modern self-understanding.

In a nutshell, what Gebser succeeded in demonstrating through painstaking documentation and analysis was this: Hidden beneath the apparent chaos of our times is an emergent new order. The disappearance of the pre-Einsteinian world-view. with its creator-god and clockwork universe as well as its naive faith in progress. is more than a mere breakdown. It is also a new beginning. In fact, long before the apostles of a "new age" arrived on the scene, Jean Gebser spoke of our period as one of the great turning points in human history. What makes his work so appealing and relevant is that it offers a unique perspective on human history and the present global crisis. When Gebser's study on the unfolding of human consciousness was first published it was considered one of the most controversial intellectual creations of our era. This is still true; his ideas challenge not only those of the establishment but also many of the new contenders.

Who was Jean Gebser? And why are a growing number of people excited about his ideas? Until seven years before his death at the age of sixty-two, Gebser was almost completely ignored by the academic establishment. It was then that the University of Salzburg, a venerable institution in Austria, created a special professorial chair for him-comparative culturology. This unique appointment was a belated acknowledgement of his genius. But it changed little, if anything, in Gebser's lifestyle; he had lived and worked most of his life as a maverick.

It is hard to classify Gebser. Neither he nor his books fit any existing stereotype. He was a scholar, a linguist, a translator, a poet, a historian, an eloquent speaker, a traveler, an adventurous lover of life, people, and ideas-a man of experience, wisdom, spiritual depth, and charisma. Gebser had many friends and admirers, among them psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, biologist Adolf Portmann, physicists Werner Heisenberg and Carl Friedrich von Weizsacker, as well as Tibetologist and spiritual leader Lama Anagarika Govinda. It was the last-mentioned who described Gebser as "one of the most creative and stimulating thinkers of modern Europe." Most important, however, are Gebser's publications and lectures, which have affected tens of thousands of people in the German-speaking countries of Europe.

Today, more than a decade after his death, Gebser is being discovered by the Anglo-American world. Annual conferences dedicated to his work are held at Ohio University under the auspices of the International Jean Gebser Society. The participants include philosophers, communication scientists, linguists, sociologists, and political scientists. Since the publication of Gebser' 5 magnum opus in English by the Ohio University Press, first in hardcover (1985) and then in paperback (1986) under the title The Ever Present Origin;', independent' study groups have started to spring up in different states. The demand for this massive volume has been such that a second printing was done in 1988. Other works by Gebser are in the process of translation. A Gebser newsletter is published in Illinois, scholarly studies on his ideas have appeared, and doctoral dissertations are being written on him.

Gebser was born in Prussia (now Poland) in 1905. He inherited his studious nature from his father, a jurist and author, and his more vivacious side from his beautiful femme fatale mother. He was an excessively sensitive child, and in a remarkable autobiographical essay, Gebser speaks of his childhood years as years of dormancy. "At that age," he writes, "there is only the connection to one's parents. That is our world."

And for Gebser, that world was one of increasing domestic conflict. When Jean was seventeen his father died of the injuries incurred when he jumped out a window in a suicide attempt. Later, in a diary entry of 1941/42, Gebser would note, "Family and country are the two main impediments to individual development." The death left his well to-do family in ruins-Gebser was forced to abandon his schooling and become an apprentice at a bank. He could bear the drudgery and boredom only because in his spare time he attended lectures at Berlin University. During that time he discovered Rilke, Schopenhauer, and Freud. (Of Freud he wrote, "...an excellent guide into Hades, but does he also lead us out of it?") As soon as he had completed his apprenticeship, Gebser left the monotony of the corporate world behind, dedicating himself to the muses. He had tinkered with his first novel at the age of eleven, and now he could pursue his passion for literature and books.

What he could not foresee was that Europe was preparing for its darkest hour. In 1929 Gebser decided to leave Germany, embarking on his pilgrim years. In Munich he had witnessed the first "brown hordes" of the Nazis, and what he saw filled him with horror. After a brief spell in Italy he went to Spain, where he lived for six years. He befriended and worked closely with Garcia Lorca and other poets, whose works he translated into German. Only his astonishing inner flexibility and linguistic facility allowed Gebser, a writer, to acculturate so quickly and successfully.

Twelve hours before his apartment in Madrid was bombed in the fall of 1936, Gebser again abandoned everything. He went into exile in Paris, where many other intellectuals were seeking refuge. There he shared the company and the poverty of giants such as Pablo Picasso and Andre Malraux. World War II erupted with a vengeance, so Gebser, who saw in war the ultimate absurdity of which humans are capable, decided to leave France. Two hours before neutral Switzerland closed its borders in August 1939, he crossed into safety, if renewed uncertainty.

It was in Switzerland that Gebser finally found a permanent home, though having been repeatedly uprooted made him sense that we must find our roots elsewhere than in geography or culture. As he puts it in one of his poems, written in the mid-1950s, " real living-at-home is only/in the hearts of those who love.

In the following decades, Gebser worked tirelessly to give shape to his inner vision. At first he focused on his poetry and on the literary works and political struggles of the Spanish friends he had left behind. He published a study of Rilke, and then began his long career as a social critic and visionary.

In the winter of 1931, Gebser had received in a flash of inspiration the concept of his later work, and now he was dedicating his life to making explicit what he had intuitively grasped in that moment. What he had realized was that the phenomenal transformations in the arts and sciences during the first three decades of the twentieth century amounted to a change in the very consciousness of humanity, in the way we perceive ourselves and the world. He compared it in its significance to the transmutation that ancient humanity had passed through at the time of Socrates in Greece, Lao-Tzu in China, and Gautama the Buddha in India. Gebser saw that early period as a transition from what he came to call the mythical structure to the mental-rational structure of consciousness. He felt that the restructuring he was witnessing in his own time was an equally fundamental shift from the mental-rational structure to the arational aperspectival structure of consciousness. Remarkably, he formulated this essentially positive concept at a time when entire nations were in shambles, and when Oswald Spengler's predictions about the doom of Western civilization were capturing the feverish imagination of the public. In a diary entry of 1941, Gebser affirmed: "Our era is, despite or because of its visible destruction's, an era of overflowing formative fullness.' His words still ring true today.

Gebser thus anticipated the key notion behind the so-called Aquarian conspiracy. Unlike so many human potential advocates, however, Gebser never thought for a moment that the emergent consciousness would necessarily usher in a utopian paradise where today's complex problems would all be solved automatically. Rather, he frequently spoke of the initiatory birth pains that contemporary humanity would have to pass through before the new consciousness could become a reality.

In characterizing the emergent consciousness as arational (as opposed to irrational) and aperspectival, Gebser sought to indicate that it transcended the dualistic, black-or-white categories of the rational orientation to life. Rationalism, for him, was by no means the pinnacle of human existence, but, on the contrary, an evolutionary digression with fatal consequences. He regarded it as a deficient of the inherently balanced mental structure of consciousness. In other words, Gebser did not reject reason, merely its inflation into the sole arbiter of our lives. As he recognized, the human being is a composite of several evolutionary structures of consciousness, and we must live all of them according to their intrinsic value. The individual who is dominated by the rational structure represses all other structures, which are viewed as irrational and hence dispensable. Thus the "reasonable" person is inclined to reject magic, myth, religion, feeling, empathy, and not least ego-transcendence.

In a 1955 diary entry, Gebser observed, "Becoming an ego is painful. Hardly anyone finds his ego prior to the middle of his life. Then most people remain stuck in it and become hardened in it. The still more painful process of ego-transcendence with all its crises and relapses is accomplished by only a few. But it is just this ego-transcendence that is the decisive task of human life."

The reason-dominated individual tends to be heavily ego-defensive, because identity is defined in terms of the ego-personality. The person who has broken through to the arational-aperspectival consciousness, however, sees the limitations of the ego, and is not threatened by the suggestion that he or she is more than the narrow field of awareness and angular vision that is associated with the ego. In fact, that person welcomes the idea that individuality arises in participation with the larger reality-a reality that by far eclipses the rational mind and even the feeling heart that is so often closed to the rationalist.

In 1943, Gebser published his book Abendlandische Wandlung (Transformation of the West), in which he surveyed the most significant changes in the natural and social sciences, suggesting that they point to a new constellation of consciousness and reality-perception. Six years later, he published the first part of his major work, Ursprung und Gegenwart, available in English under the title The Ever-Present Origin (see Resources, this page). In it, he concerned himself with the aperspectival foundations of our modern civilization. In 1953, the second part appeared. Here Gebser looked back into our human past, identifying and clarifying for us other similar fundamental mutations of consciousness. He distinguished four in all: the archaic structure, the magical structure, the mythical structure, and the mental structure (out of which emerged, as its deficient form, the rational consciousness during the Renaissance). Today a fifth mode or style of cognition, the a rational structure, has become a possibility that, as Gebser never tired of insisting, requires our conscious midwifery through personal and collective self-transcending practice.

Gebser's unabashedly spiritual orientation, which is unique in European philosophy, has confounded and annoyed his peers, especially those anxious to uphold the neutral rationalist standards of academia. Today, American Gebser scholars, unfortunately, tend to repeat the error of their European counterparts when they try to make Gebser into a phenomenologist of consciousness and culture, ignoring his strong spiritual communication.

I had the opportunity to present a paper on the spiritual implications of Gebser's work at the 1987 Gebser conference at Ohio University in Athens. Except for some old-timers, who had known Gebser personally, my presentation caused a stir among participants when I reported that Gebser had confided to me in a letter that he had had an enlightenment experience (satori). "It was sober," he put it, "on the one hand happening with crystal clarity in everyday life, which I perceived and to which I reacted 'normally,' and on the other hand and simultaneously being a transfiguration and irradiation of the indescribable, unearthly, transparent 'Light'--no ecstasy, no emotion, but a spiritual clarity, a quiet jubilation, a knowledge of invulnerability, a primal trust."

This satori experience surprised Gebser while he was visiting Sarnath in 1961, the place where 2,500 years ago the Buddha preached his first sermon. A year later Gebser published his Asienfibel (Primer on Asia), subsequently reissued in expanded form under the title Asien Lachelt Anders(Asia Smiles Differently), in which we meet Gebser the thoughtful traveler and bridge builder. He regarded the East/West encounter as central to our contemporary task of personal and cultural integration. He wrote, "The view that East and West are opposites is wrong. It is not permissible to apply opposite-creating rational thought in this context, which can, if we continue to persist in this faulty opposition, even lead to the suicide of our culture or civilization. West and East are complementarities. In comparison with the dual, divisive character of opposition, complementary is polar and unifying."

Gebser, as a spiritual pilgrim, also visited Tiruvannamalai in South India, where Ramana Maharshi, one of modern India's finest sages, had lived and taught until his death in 1950. But where he felt most in the presence of the emergent arational-integral consciousness was in the Pondicherry ashram of the twentieth-century philosopher-yogi and former political activist Sri Aurobindo. the creator of "integral yoga," who, incidentally, also died in 1950. Of that visit Gebser said, "There in Pondicherry is, to the best of my knowledge as far as India is concerned, the only place where the mutual flooding of rationalistic machine technology on the one hand and psycho-spiritual yoga technology on the other hand, has begun to be a radiant enrichment of both Asia and the West."

Undoubtedly, what attracted Gebser was the same clarity that he also appreciated in the Zen monasteries of Japan. According to him, clarity is an essential aspect of the arational structure of consciousness. He lived by this principle himself. Gebser stood for intensification. rather than mystical or psychedelic expansion, of consciousness. Clarity is both a means and a sign of such intensification. Gebser approvingly cited a remark by Paul Klee, one of the great pioneers of the aperspectival consciousness in art. "I begin more and more to see behind or, better, through things."

It would appear that this observation entails useful advice for anyone.